Презентация на тему: Robert Lowell

Robert Lowell

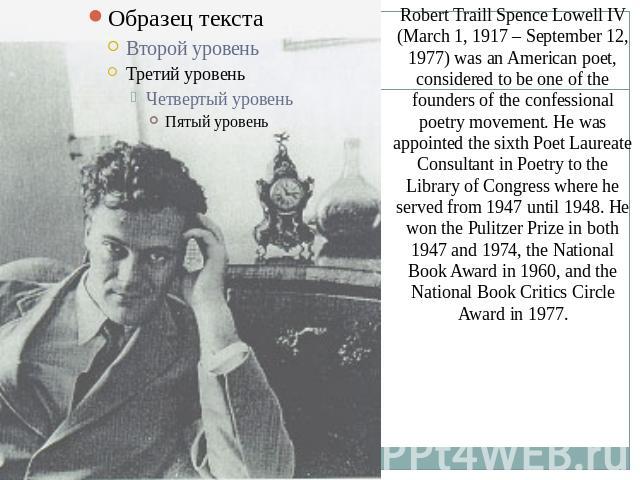

Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV (March 1, 1917 – September 12, 1977) was an American poet, considered to be one of the founders of the confessional poetry movement. He was appointed the sixth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress where he served from 1947 until 1948. He won the Pulitzer Prize in both 1947 and 1974, the National Book Award in 1960, and the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977.

Lowell fits the mold of the academic writer: white, male, Protestant by birth, well educated, and linked with the political and social establishment. He was a descendant of the respected Boston Brahmin family that included the famous 19thcentury poets James Russell Lowell, Amy Lowell.Robert Lowell found an identity outside his elite background, however. He left Harvard to attend Kenyon College in Ohio, where he rejected his Puritan ancestry and converted to Catholicism. Jailed for a year as a conscientious objector in World War II, he later publicly protested the Vietnam conflict.

James Lowell andAmy Lowell

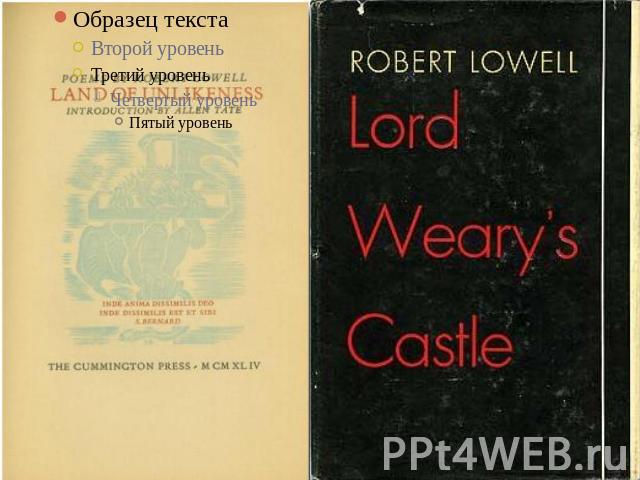

Lowell’s early books, Land of Unlikeness (1944) and Lord Weary’s Castle (1946), which won a Pulitzer Prize, revealed great control of traditional forms and styles, strong feeling, and an intensely personal yet historical vision. The violence and specificity of the early work is overpowering in poems like “Children of Light” (1946), a harsh condemnation of the Puritans who killed Indians and whose descendants burned surplus grain instead of shipping it to hungry people. Lowell writes: “Our fathers wrung their bread from stocks and stones /And fenced their gardens with the Redman’s bones.”

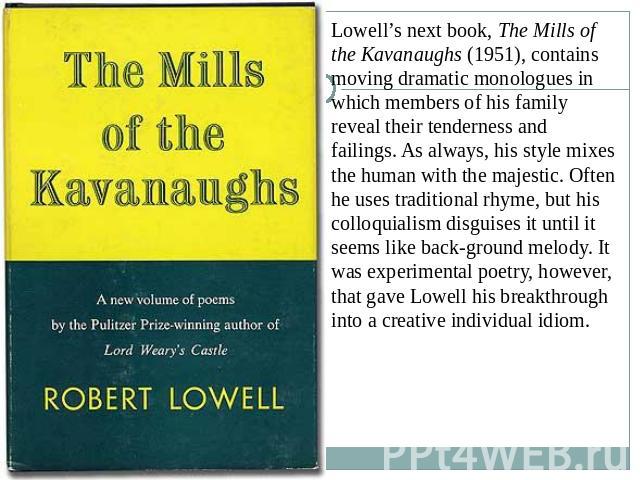

Lowell’s next book, The Mills of the Kavanaughs (1951), contains moving dramatic monologues in which members of his family reveal their tenderness and failings. As always, his style mixes the human with the majestic. Often he uses traditional rhyme, but his colloquialism disguises it until it seems like back-ground melody. It was experimental poetry, however, that gave Lowell his breakthrough into a creative individual idiom.

On a reading tour in the mid- 1950s, Lowell heard some of the new experimental poetry for the first time. Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Gary Snyder’s Myths and Texts, still unpublished, were being read and chanted, sometimes to jazz accompaniment, in coffee houses in North Beach, a section of San Francisco. Lowell felt that next to these, his own accomplished poems were too stilted, rhetorical, and encased in convention; when reading them aloud, he made spontaneous revisions toward a more colloquial diction. “My own poems seemed like prehistoric monsters dragged down into a bog and death by their ponderous armor,” he wrote later. “I was reciting what I no longer felt.”

“My own poems seemed like prehistoric monsters dragged down into a bog and death by their ponderous armor,” he wrote later. “I was reciting what I no longer felt.”

At this point Lowell, like many poets after him, accepted the challenge of learning from the rival tradition in America — the school of William Carlos Williams. “It's as if no poet except Williams had really seen America or heard its language,” Lowell wrote in 1962. Henceforth, Lowell changed his writing drastically, using the “quick changes of tone, atmosphere, and speed” that Lowell most appreciated in Williams.

Lowell dropped many of his obscure allusions; his rhymes became integral to the experience within the poem instead of superimposed on it. The stanzaic structure, too, collapsed; new improvisational forms arose. In Life Studies (1959), he initiated confessional poetry, a new mode in which he bared his most tormenting personal problems with great honesty and intensity. In essence, he not only discovered his individuality but celebrated it in its most difficult and private manifestations. He transformed himself into a contemporary, at home with the self, the fragmentary, and the form as process.

Lowell’s transformation, a watershed for poetry after the war, opened the way for many younger writers. In For the Union Dead (1964), Notebook 1967-68 (1969), and later books, he continued his autobiographical explorations and technical innovations, drawing upon his experience of psychoanalysis. Lowell’s confessional poetry has been particularly influential. Works by John Berryman, Anne Sexton, and Sylvia Plath (the last two his students), to mention only a few, are impossible to imagine without Lowell.

Lowell died in 1977, having suffered a heart attack in a cab in New York City