Презентация на тему: The history of ancient England

The history of ancient England

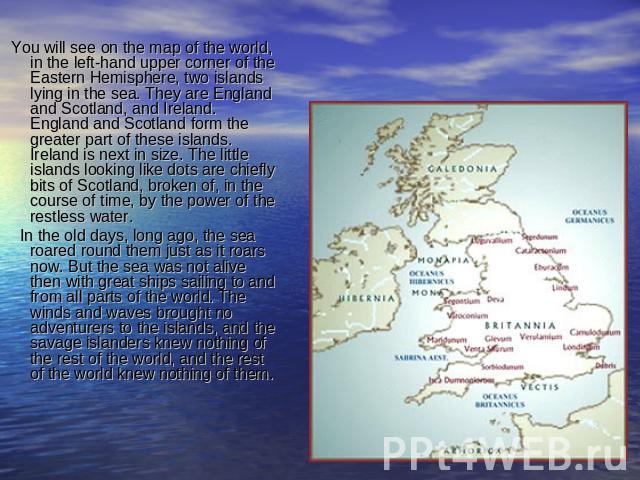

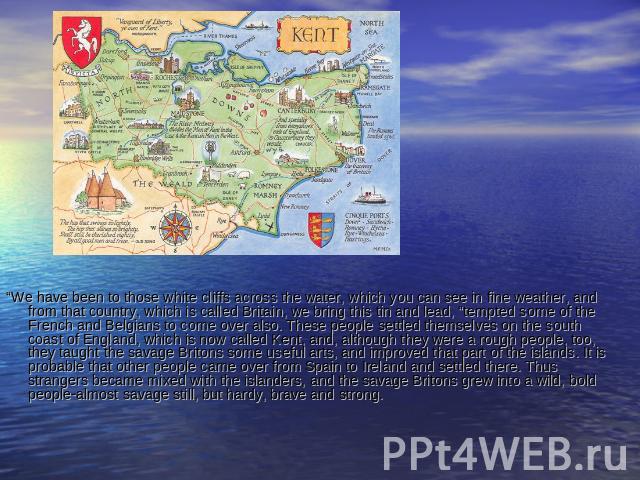

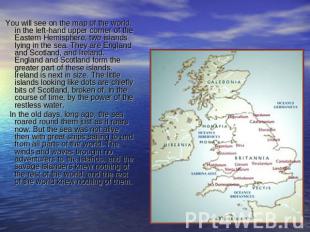

You will see on the map of the world, in the left-hand upper corner of the Eastern Hemisphere, two islands lying in the sea. They are England and Scotland, and Ireland. England and Scotland form the greater part of these islands. Ireland is next in size. The little islands looking like dots are chiefly bits of Scotland, broken of, in the course of time, by the power of the restless water. In the old days, long ago, the sea roared round them just as it roars now. But the sea was not alive then with great ships sailing to and from all parts of the world. The winds and waves brought no adventurers to the islands, and the savage islanders knew nothing of the rest of the world, and the rest of the world knew nothing of them.

It is supposed that the Phoenicians came in ships to these islands, and found that they produced tin and lead – both very useful things, produced upon the seacoast. The most celebrated tin-mines in Cornwall are still close to the sea. One of them is hollowed out underneath the ocean, and the miners say that in stormy weather they can hear the noise of the waves thundering above their heads. The Phoenicians traded with the islanders for these metals, and gave other things in exchange. The islanders were poor savages, going almost naked, or dressed in the rough skins of beasts. But the Phoenicians, sailing over to the opposite coasts of France and Belgium, and saying to the people there,

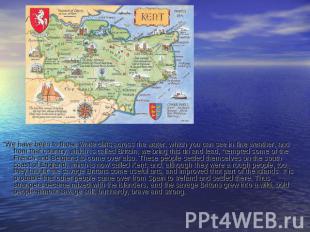

“We have been to those white cliffs across the water, which you can see in fine weather, and from that country, which is called Britain, we bring this tin and lead, “tempted some of the French and Belgians to come over also. These people settled themselves on the south coast of England, which is now called Kent, and, although they were a rough people, too, they taught the savage Britons some useful arts, and improved that part of the islands. It is probable that other people came over from Spain to Ireland and settled there. Thus strangers became mixed with the islanders, and the savage Britons grew into a wild, bold people-almost savage still, but hardy, brave and strong.

The whole country was covered with forests and swamps. The greater part of it was misty and cold. There were no roads, bridges, streets nor houses. A town was only a collection of straw-covered huts, hidden in a thick wood, with a ditch all round and a low wall made of mud, or the trunks of trees placed one upon another. The people planted little or no corn, but lived upon the flesh of their flocks and cattle. They made no coins, but used metal rings for money. They were clever in basket-work, and they could make a coarse kind of cloth and some very bad earthenware. But in building fortresses they were clever.

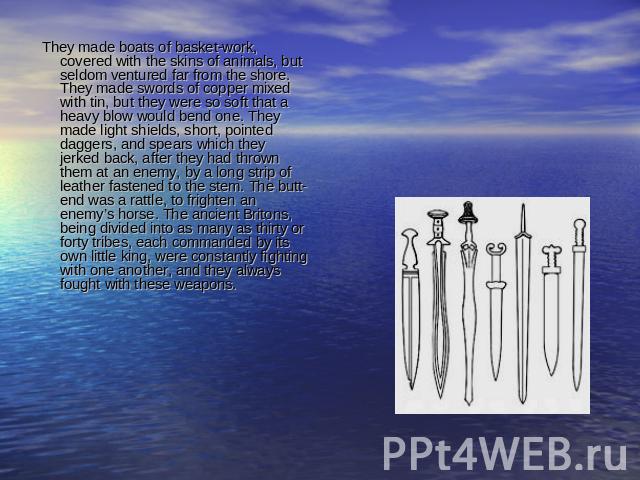

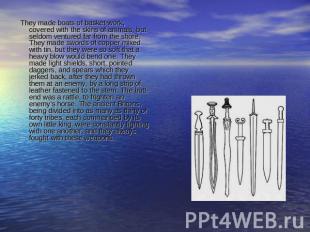

They made boats of basket-work, covered with the skins of animals, but seldom ventured far from the shore. They made swords of copper mixed with tin, but they were so soft that a heavy blow would bend one. They made light shields, short, pointed daggers, and spears which they jerked back, after they had thrown them at an enemy, by a long strip of leather fastened to the stem. The butt-end was a rattle, to frighten an enemy’s horse. The ancient Britons, being divided into as many as thirty or forty tribes, each commanded by its own little king, were constantly fighting with one another, and they always fought with these weapons.

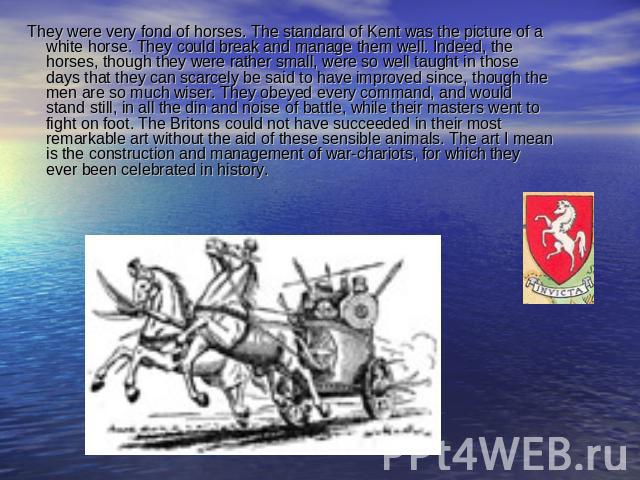

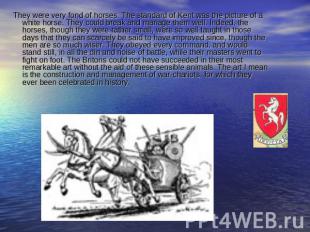

They were very fond of horses. The standard of Kent was the picture of a white horse. They could break and manage them well. Indeed, the horses, though they were rather small, were so well taught in those days that they can scarcely be said to have improved since, though the men are so much wiser. They obeyed every command, and would stand still, in all the din and noise of battle, while their masters went to fight on foot. The Britons could not have succeeded in their most remarkable art without the aid of these sensible animals. The art I mean is the construction and management of war-chariots, for which they ever been celebrated in history.

The Britons had a strange religion, called the religion of the Druids. It seems to have been brought over, in early times, from the opposite country of France, and to have mixed up the worship of the Serpent and of the Sun and Moon with the worship of some of the heathen goods and goddesses. Its ceremonies were kept secret by the priests (the Druids), who pretended to be enchanters. Their ceremonies included the sacrifice of human victims, the torture of suspected criminals, and on occasions the burning alive, in immense wicker-cages, of a number of men and animals together. The Druid priests had great veneration for the oak. They met in dark woods, called sacred gloves, and there they instructed in their mysterious arts young men who came to them as pupils.

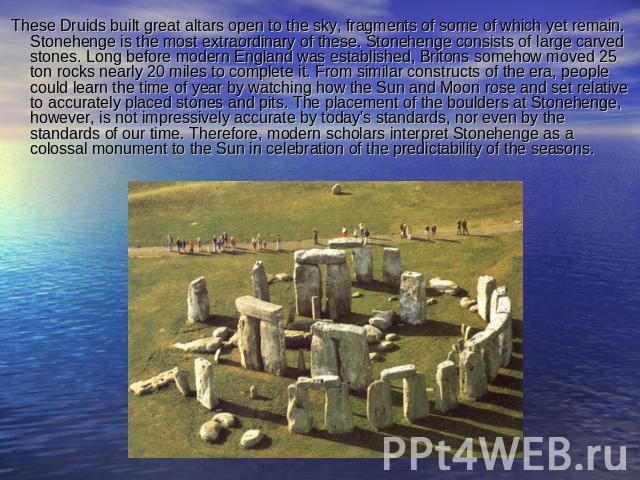

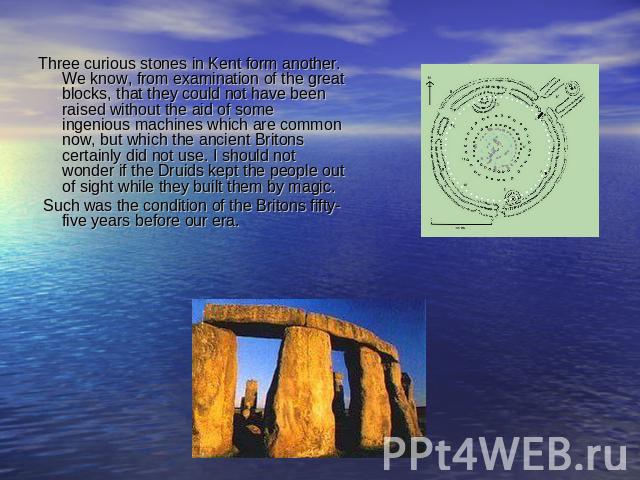

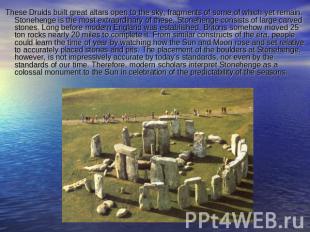

These Druids built great altars open to the sky, fragments of some of which yet remain. Stonehenge is the most extraordinary of these. Stonehenge consists of large carved stones. Long before modern England was established, Britons somehow moved 25 ton rocks nearly 20 miles to complete it. From similar constructs of the era, people could learn the time of year by watching how the Sun and Moon rose and set relative to accurately placed stones and pits. The placement of the boulders at Stonehenge, however, is not impressively accurate by today's standards, nor even by the standards of our time. Therefore, modern scholars interpret Stonehenge as a colossal monument to the Sun in celebration of the predictability of the seasons.

Three curious stones in Kent form another. We know, from examination of the great blocks, that they could not have been raised without the aid of some ingenious machines which are common now, but which the ancient Britons certainly did not use. I should not wonder if the Druids kept the people out of sight while they built them by magic. Such was the condition of the Britons fifty-five years before our era.