Презентация на тему: Whales

Whales

Contents

General CharacteristicsWhales live in all of the open seas of the world, though some occasionally enter coastal waters. Some species, such as the white whale, or beluga, may travel upstream in large rivers. The skin of whales is usually black, gray, black and white, or all white. Some, such as the blue whale, have skin that is bluish-gray. The surface of the skin is smooth, but like other mammals, whales have hair. Hair first appears while the fetal whale is still developing inside its mother's womb.

The toothed whales include more than 65 species in six different families. Among these are the true dolphins (family Delphinidae), which includes the pilot whales (genus Globicephala) and the killer whale (Orcinus orca), largest of the oceanic dolphins. Killer whales prefer coastal waters to the open ocean. They hunt in schools and, though relatively small at 30 feet (9 meters), will attack other whales two or three times their size.

The baleen whales include the family of right whales, Balaenidae, so named because whalers considered them “just right”—easy to kill and full of oil and whalebone. Among these are the black right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) of both northern and southern seas. Scientists believe that those in the western North Atlantic may be gradually increasing in numbers. However, populations in the eastern North Atlantic and in both the eastern and western North Pacific show no signs of recovery, and only a few remain in each area. An estimated 1,500 to 3,000 occur in the southern oceans, with little evidence of a significant increase in population sizes in most areas. Some scientists place the southern right whale in a separate species: E. australis. Black right whales reach lengths of 70 feet (21 meters) and are black on the upper body. The underside is sometimes paler in color. The baleen plates in the mouth may be more than 8 feet (2.4 meters) long.

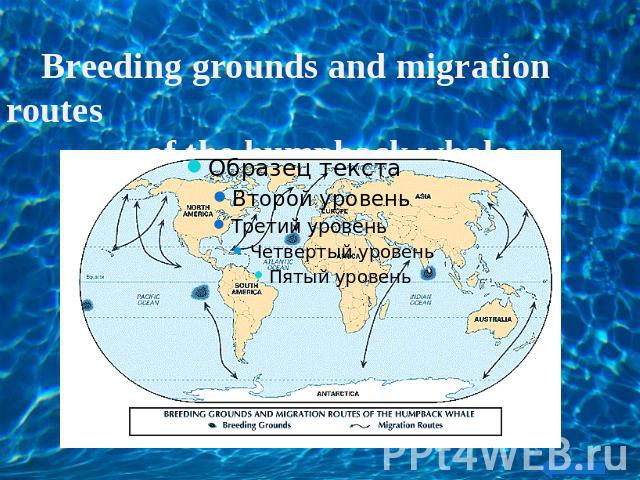

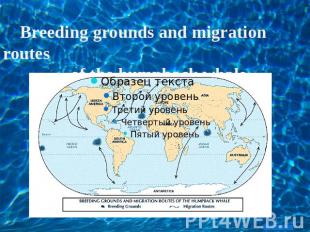

Breeding grounds and migration routes of the humpback whale

Recent studies based on genetic sequences have confirmed that all cetaceans were derived from a single ancestral stock and are closely related to the hoofed mammals in the order Artiodactyla, made up of the even-toed mammals, such as cattle, deer, and camels. Nevertheless, the evolutionary origin of whales remains controversial among zoologists. The oldest fossils clearly recognizable as primitive whales were discovered in the Eocene epoch excavation layer of sites in Nigeria and Egypt. These early forms are placed in an extinct suborder (Archaeoceti) known as zeuglodonts. Whether they are the ancestors of either modern suborder is a matter of conjecture. The largest archaeocete was Basiolsaurus, a whale from the late Eocene epoch that reached a length of almost 70 feet (20 meters). (For relative dates of the various eras, epochs, and periods see Earth.)

Archaeological evidence suggests that primitive whaling, by Inuit and others in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, was practiced by 3000 BC and has continued in remote cultures to the present. The primitive quarry were small, easily beached whales or larger specimens that came close to shore during seasonal migrations from polar feeding grounds to breed in sheltered bays. The Japanese used nets, and the Aleuts used poisoned spears. The Inuit successfully hunted large whales from skin boats, employing toggle-headed harpoons attached by hide ropes to inflated sealskin boats. In Europe, the Nordic people hunted small whales, and Icelandic laws dealt with whaling in the 13th century.The forerunners of commercial whaling were the Basques, who caught black right whales as the animals gathered to breed in the Bay of Biscay. When seaworthy oceangoing ships were built in the late 14th century, the Basques set off in search of other whaling bays and found them across the Atlantic in southern Labrador.

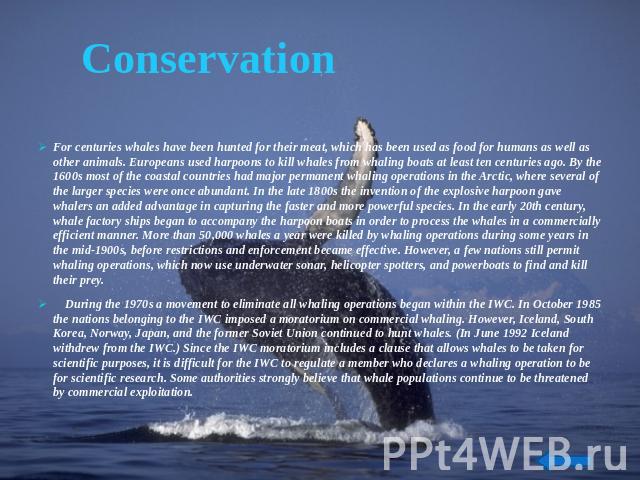

For centuries whales have been hunted for their meat, which has been used as food for humans as well as other animals. Europeans used harpoons to kill whales from whaling boats at least ten centuries ago. By the 1600s most of the coastal countries had major permanent whaling operations in the Arctic, where several of the larger species were once abundant. In the late 1800s the invention of the explosive harpoon gave whalers an added advantage in capturing the faster and more powerful species. In the early 20th century, whale factory ships began to accompany the harpoon boats in order to process the whales in a commercially efficient manner. More than 50,000 whales a year were killed by whaling operations during some years in the mid-1900s, before restrictions and enforcement became effective. However, a few nations still permit whaling operations, which now use underwater sonar, helicopter spotters, and powerboats to find and kill their prey. During the 1970s a movement to eliminate all whaling operations began within the IWC. In October 1985 the nations belonging to the IWC imposed a moratorium on commercial whaling. However, Iceland, South Korea, Norway, Japan, and the former Soviet Union continued to hunt whales. (In June 1992 Iceland withdrew from the IWC.) Since the IWC moratorium includes a clause that allows whales to be taken for scientific purposes, it is difficult for the IWC to regulate a member who declares a whaling operation to be for scientific research. Some authorities strongly believe that whale populations continue to be threatened by commercial exploitation.